Back in February, it was exposed that changing the date of your iPhone could brick the device. Now it’s been discovered that a similar threat exists over wifi as well, as the devices try to sync their time with an NTP server.

Brian Krebs from krebsonsecurity.com goes into more detail about this:

If you use an Apple iPhone, iPad or other iDevice, now would be an excellent time to ensure that the machine is running the latest version of Apple’s mobile operating system — version 9.3.1. Failing to do so could expose your devices to automated threats capable of rendering them unresponsive and perhaps forever useless.

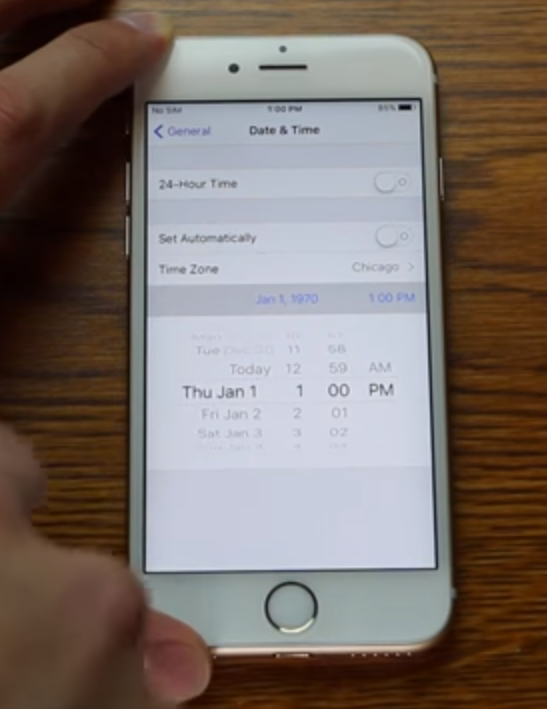

Zach Straley demonstrating the fatal Jan. 1, 1970 bug. Don’t try this at home!

On Feb. 11, 2016, researcher Zach Straley posted a Youtube video exposing his startling and bizarrely simple discovery: Manually setting the date of your iPhone or iPad all the back to January. 1, 1970 will permanently brick the device (don’t try this at home, or against frenemies!).

Now that Apple has patched the flaw that Straley exploited with his fingers, researchers say they’ve proven how easy it would be to automate the attack over a network, so that potential victims would need only to wander within range of a hostile wireless network to have their pricey Apple devices turned into useless bricks.

Not long after Straley’s video began pulling in millions of views, security researchersPatrick Kelley and Matt Harrigan wondered: Could they automate the exploitation of this oddly severe and destructive date bug? The researchers discovered that indeed they could, armed with only $120 of electronics (not counting the cost of the bricked iDevices), a basic understanding of networking, and a familiarity with the way Apple devices connect to wireless networks.

Apple products like the iPad (and virtually all mass-market wireless devices) are designed to automatically connect to wireless networks they have seen before. They do this with a relatively weak level of authentication: If you connect to a network named “Hotspot” once, going forward your device may automatically connect to any open network that also happens to be called “Hotspot.”

For example, to use Starbuck’s free Wi-Fi service, you’ll have to connect to a network called “attwifi”. But once you’ve done that, you won’t ever have to manually connect to a network called “attwifi” ever again. The next time you visit a Starbucks, just pull out your iPad and the device automagically connects.

From an attacker’s perspective, this is a golden opportunity. Why? He only needs to advertise a fake open network called “attwifi” at a spot where large numbers of computer users are known to congregate. Using specialized hardware to amplify his Wi-Fi signal, he can force many users to connect to his (evil) “attwifi” hotspot. From there, he can attempt to inspect, modify or redirect any network traffic for any iPads or other devices that unwittingly connect to his evil network.

TIME TO DIE

And this is exactly what Kelley and Harrigan say they have done in real-life tests. They realized that iPads and other iDevices constantly check various “network time protocol” (NTP) servers around the globe to sync their internal date and time clocks.

The researchers said they discovered they could build a hostile Wi-Fi network that would force Apple devices to download time and date updates from their own (evil) NTP time server: And to set their internal clocks to one infernal date and time in particular: January 1, 1970.

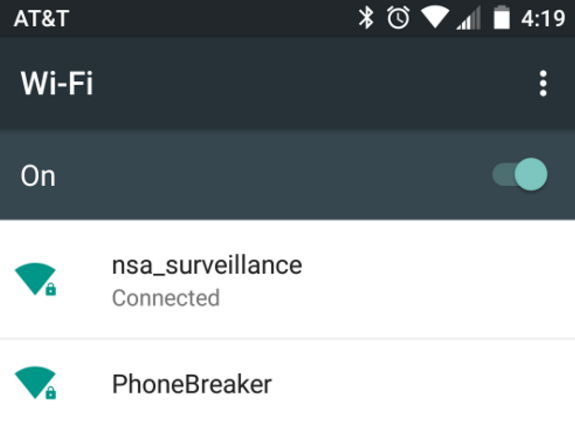

Harrigan and Kelley named their destructive Wi-Fi test network “Phonebreaker.”

The result? The iPads that were brought within range of the test (evil) network rebooted, and began to slowly self-destruct. It’s not clear why it does this, but here’s one possible explanation: Most applications on an iPad are configured to use security certificates that encrypt data transmitted to and from the user’s device. Those encryption certificates stop working correctly if the system time and date on the user’s mobile is set to a year that predates the certificate’s issuance.

Harrigan and Kelley said this apparently creates havoc with most of the applications built into the iPad and iPhone, and that the ensuing bedlam as applications on the device compete for resources quickly overwhelms the iPad’s computer processing power. So much so that within minutes, they found their test iPad had reached 130 degrees Fahrenheit (54 Celcius), as the date and clock settings on the affected devices inexplicably and eerily began counting backwards.