This bit of history just in from BBC news, bbc.com,

For nearly 75 years BBC staff at a sprawling stately home on the outskirts of Reading have been listening in to some of the world’s most seismic events, from the rise of the Nazis to the death of Stalin and the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Since 1943 Caversham Park has been the home of BBC Monitoring, whose offices still summarise news from 150 countries in 100 different languages for the BBC.

But after a £4m funding cut, the remaining journalists, academics and translators are to leave the country estate for new offices in London.

As the international newsgathering service enters a new chapter of its life, BBC News examines how Caversham Park shaped the news agenda in the mid-20th Century.

World War Two

The monitoring service began at the outbreak of war with Germany in 1939, with its primary purpose to inform the War Office of propaganda by Nazi-controlled media outlets and the broadcasts of other Axis Powers.

It initially set up camp in shacks around Wood Norton, Worcestershire, but by 1943 the service had commandeered Caversham Park, which was at the time being used as a hospital.

The recorded history of the site goes back to the Domesday Book, when it was inhabited by relations of William the Conqueror, but by the 20th Century it was being used by the Catholic Oratorians as school. By 1941, the premises had been transferred to the BBC.

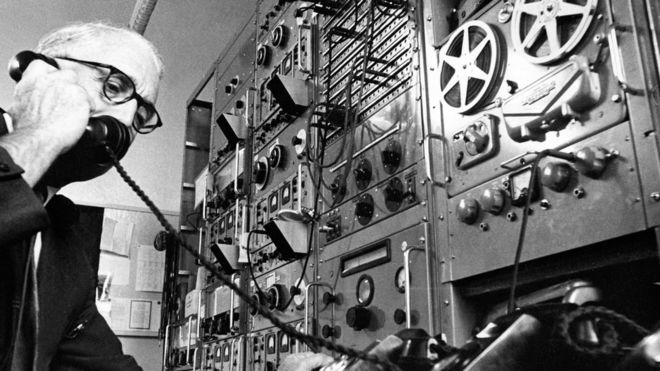

Monitoring staff at Caversham would transcribe and summarise 240 broadcasts into an 80,000-word document called the Daily Digest. This was swiftly delivered to London by war despatch drivers.

BBC Monitoring played a key role in tapping communications made by Hellschreiber (a kind of teleprinter) from Nazi Germany’s propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels to newspaper and radio networks. A site outside London was chosen in part because it was less likely to suffer bomb damage.

By the end of the war 1,000 people worked at Caversham Park helping to provide the War Office and BBC journalists with up-to-date information from Axis Power news agencies.

People of many nationalities worked at the monitoring station, including German-Jewish refugee Karl Lehmann, whose family fled Nazi rule.

He said: “It was a very sociable place to work, in fact staff would often come in on their off days and eat in the canteen, which greatly eased the effects of rationing.

“There was a library in the building, and the park – so a pleasant place to spend a day off. In fact the building was almost like a club and the service was like one big family – even though there were nearly 1,000 of us here in total, from monitors to engineers and editors.

“We were all totally united in the one aim of winning the war.”