There is a big difference between filing for a patent for your idea, and establishing it as a trade secret.

A patent, by it’s very nature, requires that you reveal details about how it works, what it is, what it does. This information must be revealed in order to gain a patent. A definition of a patent would be a set of exclusive rights granted… to an inventor or their assignee for a limited period of time, in exchange for the public disclosure of the invention. (The telephone- often considered the most valuable patent.)

A trade secret, on the other hand, is exactly that- a secret. No one but you should know what it is, or how it works. It is required to be kept secret, private, and confidential. It must be protected, otherwise it cannot be considered a trade secret. (The formula for Coca-Cola- the most famous trade secret.)

Here are some other significant points- a patent has a time limit, it is good for only 20 years, but during that time, it may not be copied by anyone else. Someone stumbling upon the same idea independently or reverse engineering your product will not be allowed to use it. The well kept trade secret on the other hand, can last forever. The risk, though, is if someone figures out your trade secret on their own, they can still use it. But if it can be determined that your competitor’s information was obtained improperly or through some form of espionage, you will be able to bring judgement against them. Sweeping your facilities for eavesdropping threats is one important step in establishing that protection.

The following article sheds good light on this issue.

Harvard Business Review Blog Network

Filing for a Patent Versus Keeping Your Invention a Trade Secret | by Orly Lobel | November 21, 2013

For many years, beginning in 1942, Premarin was the only hormone replacement therapy drug on the market derived from a natural source. The drug, provided as a treatment for negative symptoms of menopause, became the most widely prescribed drug in the US and Canada during that time. Wyeth, a pharmaceutical acquired by Pfizer in 2009, was the sole supplier of Premarin. A series of patents were issued on the drug in the 1940s, but long after they had expired, there were still no generic competitors on the market. How could Wyeth sustain this exclusivity for such an extended period of time, decades beyond the 20 years of the patent’s term?

The answer is that no one succeeded at duplicating the extraction process, which Wyeth had not patented, but rather kept as a trade secret. The key ingredient in Premarin is conjugated estrogens extracted from pregnant mare urine. That’s right. The secret sauce of the multimillion drug is horse pee, and the process for extracting the equine estrogens was kept in Wyeth’s manufacturing plant in Brandon, Canada. While heated debates continue over the impact of the patent wars on market competitiveness, the implications trade secrets are more likely to be misunderstood. Trade secrets are thought to be the real workhorse of the knowledge economy, because of their pervasive importance. At the same time, trade secrets are viewed as the stepchild of intellectual property because they operate, by definition, in secrecy, and we know much less about their role in market competition than we know about patents, copyrights, and trademarks.

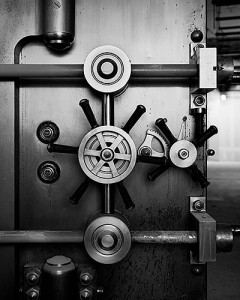

Why do some companies choose to patent their innovation while others choose to hide it? Compare the paradigmatic early American trade secret, the one and only recipe for Coca Cola – to the paradigmatic patent, the telephone. Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone in 1876 as United States Patent No. 174,465, the most valuable patent in history. Ten years later, in 1886, Dr. John Pemberton created what is now the world’s most famous trade secret: the Coca-Cola formula. Insiders know it as Merchandise 7X. No single contractor has the full recipe; each is tasked to prepare only parts of the classic blend. The company has kept the secret for over a century by purportedly storing it in a vault in downtown Atlanta, and restricting access to only a handful of executives. Coca Cola could have patented the formula, but that would only give the company twenty years of exclusivity rights to their classic taste. Instead the formula is locked up, literally and indefinitely.

A well-kept trade secret could theoretically last forever. But there is a risk. Unlike with patents, it is perfectly legal to reverse engineer and copy a trade secret. A patent lasts only 20 years, but during that period, the protection is far stronger: independent invention is no defense in a patent suit. In 1998, a group of horse ranchers suddenly set up a production facility and filed an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) for a generic version of Premarin. They claimed to have succeeded in mare urine extraction where others had failed. This, of course, represented a serious threat to a hugely profitable product. If the horse ranchers had indeed been independently and honestly lucky in their discovery, Wyeth would have lost its market dominance. Such was not the case. Wyeth launched an extensive, and expensive, investigation leading to evidence that the horse ranchers had improperly encouraged one of Wyeth’s own former scientists to provide the secrets to the manufacturing process. The court issued a sweeping and devastating judgment against these new competitors, ordering a permanent stop to the use of the trade secret.

Patents and trade secrets present opposing choices. Trade secrets derive their legal protection from their inherently secret nature. Patents, by contrast, can only be protected through public disclosure. In fact, a patent will be invalidated if the inventor refrains from describing important details. This requirement, called enablement, requires a patentee to disclose enough information for others to use the invention after the patent has expired.

Budget constraints and the costs for filing a patent force a smart evaluation of your options. When facing the choice of patenting or hiding a valuable innovation, you must first ask yourself whether the invention is patentable at all. Does is it meet the legal requirements of non-obviousness, novelty, and usefulness to be granted a patent? Even if it does, ask yourself:

- Will the invention be useful beyond 20 years?

- Is it possible for other companies to reverse engineer it?

- Is the invention detectable and embedded in the product itself or is it part of an internal manufacturing process?

- Is the invention likely to be independently discovered in the near future?

- Is the product regularly observed in public settings?

The answers to these questions are company- and invention-specific. A company that has high turnover among its employees and that uses a range of partners in its production process might rightly fear going the path of trade secrets.